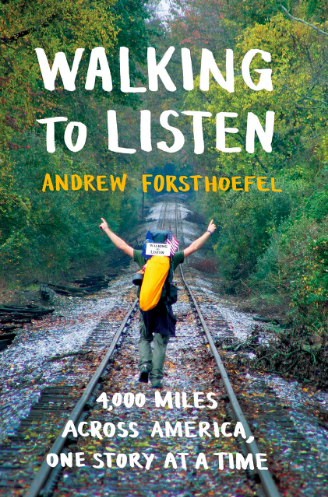

We’re thrilled, and truly honored, to continue traveling “Through the Realms” with Andrew Forsthoefel, speaker, peace activist and author of Walking to Listen: 4,000 Miles Across America, One Story at a Time (March 2017).

After graduating from Middlebury College in 2011, at the age of 23, Andrew walked out the back door of his mother’s home in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania with a backpack, mandolin, audio recorder, copies of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, and a sign that read “Walking to Listen.” He spent the next 11 months walking across the United States, listening to the stories of strangers and seeking tidbits of wisdom that would usher him into adulthood and help guide him on life’s journey.

“I wanted to learn what it actually meant to come of age, to transform into the adult who would carry me through the rest of my life,” he writes. “I wanted to meet that man. Who was he? What did he know? How would he finally become himself, and where did he belong?”

Andrew’s book, Walking to Listen, chronicles his 4,000-mile trek in a beautifully written narrative that shifts between his own inner dialogue and the stories of the strangers he encounters. Containing profound insights on the human condition – from fear and doubt, to love and loneliness – it surprises even the optimist with the marvelous acts of kindness he bore witness to on his journey.

We asked Andrew to sit down with us for a Q&A, and are delighted to share his responses:

1. One of the things that most struck me in reading your book was the bravery you exemplified in pursuing this challenge. Particularly in a society that often tries to dictate our path – go to college, graduate, get a job, etc. – I was moved by your openness and willingness to, quite literally, forge your own path.

Can you share a little bit about what motivated you to set off on this walk? What sort of resistance did you face, if any? Did you view it as a risk or something you felt compelled to do?

In the weeks before I set out, I struggled to understand the why of what I was about to do, and therefore struggled to put it to words. It was, as you say, something I felt compelled to do. What I realize now is that when you are setting out on a journey, you can’t really know why you’re about to do it. You can come up with some reasons that might seem to explain the longing that is calling you out, but those explanations are just your mind’s best attempt at controlling the situation by interpreting it and presuming to know something about it. Which my mind certainly did. I decided I was walking to listen. I wanted to slow down and really be with people, see them as extraordinary, look to them as if they were my teachers. A worthy reason to set out, for sure, but not the real reason, or not the whole reason. The reason I set out was revealed to me as the walk unfolded, with each new person I met. Each moment was an answer to the question, “Wait, why am I doing this again?” If it was a miserable wet night alone in South Carolina: This is why I am walking, to experience this, learn this, be with this. Or if it was an ecstatic night camped out on the rim of the Grand Canyon: Same answer. It was about touching the vast spectrum of experience available to us as human beings, rather than staying in the few familiar shades. That spectrum included (and includes) everything—from the people who looked different than I did, to the people who believed different than I did, to the earth and the elements, to the invisible ecosystem of my mind . . . I was walking and listening to learn and receive whatever and whoever I encountered. And so of course I couldn’t know why I was doing it, when I set out from home. Thankfully, I didn’t have to. That was a revelation: I don’t always have to know why I’m going to do something in order to do it, and even if I think I know why, I will likely learn more about why as I go. And that’s okay. That’s normal. I don’t have to have it all figured out at the start, or in the middle, or even at the end.

My family and close friends were all very supportive. I didn’t have anyone in those circles telling me that I was about to make a big mistake. What a blessing it is, to be believed in, to be trusted. And to believe in yourself, to trust yourself. That was where most of my resistance came up: myself. So that was the practice: watching the doubt come in, listening to it in the same way that I tried to listen to the people on my walk, which didn’t mean I agreed with them, but did mean I wasn’t trying to change them, fix them, or eradicate them. The same with the doubt. I was learning how to be a faithful witness to doubt, too. I wouldn’t have said this at the time, though. At the time, I thought doubt was bad. I thought it was possible for things to be bad: parts of myself, or certain people, or the weather. Now, I don’t see anything as bad, which isn’t to say there aren’t excruciating, confusing things that happen. They do. But to dismiss them as simply bad is to miss out on whatever it is they have brought for me. What is it here to teach? What is it asking for? You can take this approach and apply it to everything. For instance, if I am anxious, I can ask: What is this anxiety asking of me? Why is it here? What is it telling me, underneath the surface-level agitation? What is it showing me about where I should go and how I should proceed? This kind of inquiry, this perspective, can be the gift you offer to each one of your relationships, and you are in relationship with everything.

I’m thinking now of Bryan Stevenson, an activist lawyer and author I got to meet in Montgomery during my walk. He has a brilliant line that speaks to this, applied in the realm of the interpersonal dynamics of society: “Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.” It complicates the notion that something or someone could be simply, unalterably, absolutely bad. As this notion begins to fall apart, so does its polar opposite: the notion that something or someone could be good. Once I began to understand that the dichotomy of good and bad isn’t true, I became less interested in walking to find some sort of answer that would make me good or somehow better than I already was, and instead, I became more curious about who I actually was, who I actually am, which is inclusive of everything that comes into the field of my awareness. It changed how I interacted with people, too. There were no good people and no bad people. There were just people, each of us complicated, contradictory, suffering, struggling, and longing to be home.

2. Throughout your book, you talk about the intensity of silence and solitude, but also the liberation that comes from being unplugged. A month into your journey, you head into a grocery store and realize how far removed you’ve been from society. Seeing the tabloids, you write: “The stuff seeped into my consciousness like poison, and something inside me railed to get back out into the unplugged inner space of walking, the wind, the arrhythmic lull of the highway. That was another privilege I was cashing in on: the privilege of going dark, of removing myself from the psychic bombardment of media and advertising that saturates America, online and off. So much noise.”

Can you talk about your relationship with solitude and silence throughout your journey and how it changed? What about today? Are there times when you crave that “darkness”? Is it possible to achieve a balance between being hyper-connected and going completely off the grid?

I was very uncomfortable in solitude at the beginning of my walk, scared to be alone. Some of that fear was projected onto the outside world: fear of being mugged or beaten, fear of being attacked by animals or hit by cars. But mostly, I was afraid of myself, which is the fear that motivates all other fears. If I am afraid of encountering myself, all of myself, than it stands to reason that I would bear some significant fear of the world, too. If I have already encountered, explored, and committed to being in relationship with the myriad voices inside my own head, then when I hear those voices coming at me from the outside in, I am not afraid. For instance, doubt again. If I am intimate with doubt as a walking companion in my solitude, if I am able to watch all the ways that doubt expresses itself, if I have asked doubt questions like “Why are you here?” and “What are you afraid of?” then I am in relationship with doubt. So, if you come at me with doubt—doubting yourself, or doubting someone else, or doubting me—it’s less likely that your doubt will resurrect mine. Because in my solitude, I’ve already seen that doubt is simply an ephemeral mind-state, a way of being for a moment, and that that’s what you’re experiencing right now, doubting. I can see that, because I am doing the work of knowing myself, which includes knowing doubt. This works happens in solitude. There isn’t anyone else who can do it for me, no one who can show up to the task of receiving and understanding whatever comes into my experience, inside and out.

Silence, I love. Although I am not always at ease sharing it with others. But I am learning, and what I’m finding is that silence makes certain things possible in conversations that wouldn’t happen otherwise. Try giving someone silence, as you connect and listen. Not in a weird, I’m-not-allowed-to-talk kind of way, just aligning yourself with the intention to listen, rather than be heard, and see what happens. For me, it’s always a balancing act between giving and receiving, speaking and listening, knowing and being known. Is it time to listen? Is it time to speak? Just being mindful about when and why I choose to take a certain course of action, and being willing to explore the motivations and intentions behind my choices. But I have learned that if I don’t have lots of silence and solitude weaving my days together, I start to feel agitated or depleted.

And to the last part of your question: I wonder, what is to be hyper-connected? What is connection? To me, connection has nothing to do with how many friends or followers I may have in virtual reality or even in reality itself. Connection doesn’t concern itself with numbers, and it doesn’t exclude, which means that it is not mutually exclusive with social media, and it’s not partial, either, which means it doesn’t necessarily prefer the darkness off-the-grid. I think this balance of connection isn’t about assuming it has to look a certain way, but instead about getting honest with ourselves about what, in truth, nourishes us, takes us home, awakens us to our most transparent self. It is about listening to ourselves, which, for some reason, isn’t always easy. It is about sensitizing ourselves to the forces of disconnection like canaries in coal mines, which is the work of becoming yourself, and only you know how to proceed with that work with and for yourself.

3. The idea of home is a running theme throughout your book. You speak of home as both a physical place – the house you grew up in – but also a state of mind, fueling your walk. You write, well into your journey: “Home was here. Home was this. Home was now. There could be no other answer, but something about that felt disappointing. Home was supposed to be solid and unchanging, not the unpredictable fluidity of the present…[h]ome probably had something to do with forgiveness, moving on from the resentment that made me want to keep seeking until I became someone else altogether, with a different story and a better home that was always just a little further off.”

Is this notion of “finding” home synonymous with seeking inner peace? With accepting ourselves for who we are in this moment? How can we reconcile our perceived notion of what “home” should be with what it often ends up being?

Ultimately, I do see home as the work of peace, and there can be no outer peace without inner peace, so I’m not sure the two are separate.

What if home really was the experience of a specific place with specific people? How unreliable such a home would be, given that place and people are constantly changing. Where would your home really be, in all that flux? The question I started asking myself was: must all the conditions outside myself align in a very particular way in order for me to experience this thing we call home? Do I need to be in a certain place with certain people to be at ease, to be fully myself, to show up? Or, can I, in every moment, be coming home? Can I be a good host, wherever I am, taking care of my garden that is the present? In this garden, all kinds of flowers and vegetables are growing, fruits and nuts and herbs. Every person you meet. Every thought you think. Every kind of weather. If I do not see each piece of every moment as a part of my garden, my home—which is to say, as something in need of my attendance, devotion, listening, and gratitude—then I become more inclined to treat certain places and people as inferior, as less-than-home. I become stuck in the delusion of home as some other place out there, where things are somehow better. And in so doing, I reject everything else as somehow worse, or unworthy, which is an act of violence. It’s a chorus of “not good enough, not quite right, not it, not home” in my head, and I’m back into a paradigm of false separation that does not recognize the underlying interdependence and interconnectedness of everything and everyone. So yes, home as a practice. Home as a meditation.

That being said, it is very grounding to practice homecoming in a particular place, with a particular village. To become of the land, for the land. To know the rhythms and intimacies of a unique little corner of the universe, and to, in a sense, become that corner. I am only now beginning to learn home in this way.

4. Of all the places you passed through, Alabama – particularly Selma – seemed to evoke the greatest depth of emotion. You write, “Alabama made my head swirl – the hatred, the kindness, the separation, the interdependence, the complete lack of resolution. I was walking through a land imbued with pain.” You go on to write: “I recorded more interviews in Selma than anywhere else in the country. I stayed for three days and bounced around between Church’s Chicken and a few actual churches, the police station, a museum, the welcome center. I listened to anyone who wanted to talk.”

What was it about Selma, or Alabama, that spoke to you in such an evocative way?

I walked to Selma from Montgomery, retracing the same path that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and hundreds of others walked in 1965 in non-violent protest of institutionalized racism, and, underneath that, in recognition of the truth that we are all human, equal, needed. Walking that path (in reverse), imagining all of them together, seeing where they slept at night, and even where one of them was murdered by the KKK on the side of the highway . . . it had the effect of making it all real for me, or of shoving my face into the reality of it. My body was where their bodies had been. And when I got to Selma, my body was in the jail cell where Dr. King’s body had been, and in Brown Chapel, where their bodies began the march. The spaces were all the same, and once I got in those spaces, time seemed to shrink a little, and it was like I could hear their voices. And in a very real way, I could. Many of the people who were alive during the Civil Rights Movement were still alive when I passed through Selma, and I got to listen to them.

I think I was so touched by Selma, and all of Alabama, because I was so far from the sterilized container of a classroom, or the barricaded fortress of my social bubble, and I was out in this other world, my country, exposed to the stories and realities of people I simply wouldn’t have met otherwise. People with whom I empathized. People with whom I really disagreed. A wide-ranging spectrum of people, and just like any ecosystem needs biological diversity for homeostasis, the ecosystem that was me needed that diversity for equilibrium—exposure to a diversity of ideas, stories, histories, accents, tastes, opinions, interpretations, wounds, laughter. In Alabama, it’s like my soul got to blossom because there was so much fertilizer, such diversity. It hurt, much of the time, but the hurt was a good hurt, because I was walking in and through and with the truth: the face-to-face, human-to-human truth of our messiness and our beauty, in all its contradictions and complexities, especially through the lens of race, racism, and the legacy of slavery. As a white man, this truth was not something I was forced to look at over the course of my life, in the way that people of color are forced to. White privilege, one college friend informed, is the luxury of not having to constantly think about the color of your skin, the luxury of forgetting about the living legacy of our choice to invent the concept of white and black, the ability to take distance from the violence of such a perspective. In Alabama, I was brought close, I was reminded, I had to think about it.

5. One of my favorite moments in the book is when you are in New Mexico at Archie and Alexis’ house, a couple who offered you shelter for the night. You describe how when you sat down to dinner, Archie had made your chair into a sort of throne and in the center of the place setting was a mirror, forcing you to look at your own reflection. You write: “…I understood what Archie was saying. It was simple: I was what I was looking for, not someone else, some teacher or lover or friend, some epic epiphany. Not some other version of myself, either. Just me, exactly as I was seeing myself now.”

I found this moment to be incredibly powerful, and wonder if you can take us back to then? What was this moment like for you? And how have you been able to hold onto that understanding 5 years later? Is it something we can ever fully grasp, or do we have to continually relearn it, in different ways, throughout our lives?

This was a very powerful moment for me, and it took several years to sink in. Writing about it helped me put the inchoate experience of it into words, helped me understand it that way. When we walked outside and I saw the throne, I was shocked, humbled, a little confused, maybe even a little scared. It can be scary to have other people, especially adults, show up to you with such integrity, as elders, if that’s not something you’re used to. It can be intimidating and even threatening to be so deeply seen by another, seen as worthy, as needed. To be touched and held and loved: not always easy. That’s a part of what I was learning on this walk, learning how to receive and be received. It is an important skill, and not something that we inevitably know how to do. We have to learn it, or relearn it, the skill of receiving and being received. Something is lost when we forget how to do this. If, in that moment with Archie and Alexis, I had freaked out, we all would’ve missed out on that opportunity to experience love together.

A part of receiving is knowing that it’s not actually about you. It’s about the act of giving and receiving itself. It’s about the one who is offering. It’s about the exchange. If the focus of my attention in that moment was me, if I had made the throne into junk food for my ego, then that would’ve taken it away from love, too. It would’ve been nothing more than a boring, masturbatory charade, and the gift of what’s being offered wouldn’t, actually, have been received. So, I was learning how to receive (i.e. not turn a gift away out of a feeling of unworthiness or a belief that I didn’t need it) without making it about me (i.e. assuming the gift means I am superior in some way).

It seems life is made up of remembering and forgetting. Receiving this kind of gift from Archie and Alexis—a lived experience in which I had two adults delivering to me the message of my worthiness, my belonging—had the effect of making it a little harder for me to forget this message, this truth. Or a little harder to believe the other voices in my head that might try to convince me otherwise: the doubt, the self-loathing, the fear. When that stuff comes up, I have this experience with Archie and Alexis to return to, to reorient myself around. This is the point of a real coming of age ritual: to give the young person a shared experience the truth of their belonging that will act as an anchor for them when their existential seas get stormy. I can only wonder about how healing that experience was for me, because I’ll never know who I would have been without it. But I do wonder about all the sharp edges in my mind and heart that their gift was able to soften. To be trusted and loved and accepted by them (and hundreds of others across America) made it a little easier for me to trust and love and accept myself.

6. You pose a question toward the end of your book that I think is particularly poignant. It’s the part where you learn about the news of James Holmes, the man who walked into a midnight screening of The Dark Knight Rises in 2012 and started shooting, killing 12 people and injuring 70. You talk about Holmes’ brokenness and his desperate attempt, evidenced by his journal, to grapple with the existential questions we all face as humans. You then write: “Perhaps his brain was doomed from the beginning, but I think it’s misguided to blame that brain alone….[t]hat brain was raised in a society shaped by certain conventions, beliefs, and practices, a culture that influenced the way Holmes reacted to his own existence. Nature and nurture. Nature will do what it wants, but we are the nurturers. What are we nurturing in America today?”

This is an incredibly important question worth meditating on. Can you elaborate on this? What should we be nurturing, and how can we as individuals contribute to a healthier cultural nurturing?

I think we can start with listening and go from there. Start with listening and the rest will take care of itself. Don’t wait for Congress to pass some piece of legislation that will save us. Don’t wait for the doctors to figure out what medications we need. Don’t look to your priest, rabbi, shaman, imam, or guru to show you the way. Simply ask yourself: “Am I listening?” and go from there. Are you taking care of your garden, your little corner of the universe? Are you listening, deeply, to the people in your life? Are you asking them sincere questions, without assuming you know the answer, without an agenda to dominate, manipulate, control, or convince them? Are you listening to yourself in this way? Attend to that which has been entrusted to you: your life, your path, your moment. If all of us begin attending in this way, our culture will transform on its own. Such a transformation will never come from the top-down. It cannot, as the notion of top-down is a part of the cultural paradigm that is creating so much suffering. Laced into the notion of top-down is a sort of negligence, a refusal of responsibility. It is, in a way, a childish notion. “Mom will take care of it for me.” “Dad will clean up my mess.” Congress will do it or should do it. The president, the visionary, the boss. Which isn’t to say that our political and spiritual leaders aren’t responsible for doing their part. Of course, they are. But each one of us has to do our part, too, and there is no part that’s any more or less important than the other. If we are all listening—devotedly, with the intention to learn, evolve, and understand—then we’ve all got eyes on each other. We’re all being seen and heard, held and welcomed, and no one’s slipping through the cracks. And when someone does slip through the cracks, we are willing to listen to them about what it was like, to slip through the cracks.

That’s what’s not happening right now in our culture. There is not a collective willingness to listen to the pain, which is, if you are listening openly, to feel the pain. We are trying to legislate our way out of it, intellectualize our way around of it, numb and distract and fight against it. But we’ve got to go through it, because we are, after all, already in it. If we do not first stop, and open ourselves to feeling what’s actually here in this cultural moment, we won’t go anywhere new. If I can’t listen to how you are hurting, which might include your perception of me as having contributed to that hurt, without trying to defend myself or change you in any way, you and I will remain stuck. Listening to you in this way, I am doing what Archie and Alexis did for me that night with the throne: I am accepting you, trusting you, loving you. I am receiving who you are and how you are and respecting your experience of reality, rather than dismantling it as unworthy or false, based on my assumptions about what’s right and wrong and where you fit into that matrix, or more likely, just based on my fears. If I can get over myself and really listen to you, ask you questions, walk with you and for you, I have become a bridge, and I have walked out onto that bridge of myself, where I wait for you to join me, and if you don’t join me, I don’t blame you or attack you. I remain a bridge, here, waiting.

There is a reason why most of us aren’t living in this way. It doesn’t make much sense to the rational mind. It is hard and confusing and there aren’t many models for it in the mainstream. One model comes from the Civil Rights Movement, the non-violent protestors. They had the vision of a more beautiful world in their hearts, and they stayed connected to that vision even in the face of terrifying violence. The most ghastly and ghoulish faces a human can make, they witnessed. They abided in their vision, choosing not to reciprocate. I love these people for what they did, for their teachings. We do not have to reinvent the wheel. There are those who have listened in this way before.

7. I loved the different nouns you used to describe your walking throughout your journey, based on what you were experiencing and how you were feeling at the time. Among many others, you mention “float-walking”, “hurt-walking”, “craze-walking”, “dream-walking”, “howl-walking”, “why-walking”, “beauty-walking”, “read-walking”, etc. Toward the end of your book you talk about “weep-walking,” writing: “Next to beauty-walking, this was the best of them all: weep-walking, when I was feeling more than my thoughts could take and all I could do was cry. I’d never experienced anything like it before the walk, this unexpected, uncontrollable sobbing. Men weren’t supposed to do that, but the more it happened to me on the road, the more I realized how much I needed it, and how much I always had…I always tried to understand it, but I never quite could. It had something to do with walking alone in an unknown place far from home, especially after mile twenty, with a screaming body and a heart left quaking my solitude. There’s vulnerability in that pain. The opening is there, and with the right thought or image, the weep-walking enters.”

Can you talk to us a little bit about vulnerability and the role it plays in helping us to understand ourselves, and others? What about the role it plays in listening to others?

Vulnerability is the heart of the human experience. “Vulnerable” is an adjective that means “capable of being wounded,” and that’s what the heart does, it breaks, because it loves.

It is so easy to forget how central vulnerability is to who we are, or to never realize it at all, especially when our bodies are young and healthy, capable and powerful. But think about it: you are never not vulnerable, so long as you are in this body and mind. Your body is subject to injury, illness, aging, and death. Your mind is subject to all the thoughts that pass through it and become it, thoughts that create illusory worlds which, by the power of our belief in them, become real and make us suffer. We are exposed, as humans, no matter how well we disguise ourselves and shield ourselves. We are not in control, no matter how well we appear to be. We do not know which thought is going to enter our minds next, no more than we know what’s going to happen in the next moment. It could be anything. We do not know. We are vulnerable.

Vulnerability is only frightening if you’re avoiding it. Stepping into your vulnerability, which is your truth, feels good, because it’s true. It is the relief of not having to pretend or deceive anymore, of not having to be some impossible version of yourself that is unshakably happy, infallibly right all the time, and constantly winning. The delusion and disease of invulnerability. Stepping into vulnerability (which, to me, is at the core of spiritual practice and any personal work worth exploring) is when you become available to wonder, prone to learning something new and real. It is the gratitude of seeing how taken care of you are even when you are wounded.

In our culture, we have done a great violence to ourselves by telling the story that getting wounded is somehow a bad, shameful thing. One of my teachers once told me that the wound is the medicine. My wounds are the place from which I am able to connect with you in yours, the place from which I am able to understand, empathize, and be humbled. I am not a god, thank God. I am vulnerable. And so are you. When I recognize this, I am able to listen to you without expecting you to be something you’re not, remembering that you are imperfect, wounded, uncertain, insecure. You are vulnerable, just like me, and can I have compassion for that? For you? Can I be as patient and generous with you as I would hope to be treated in my own vulnerability? This is the power of vulnerability. It has the potential to craft us into heart-centered human beings, because it is the heart that opens once vulnerability is understood to be the teacher it is and not the enemy we thought it was.

8. You write beautifully. There are so many passages I could point to as examples, but there’s one in particular that has stayed with me that I’d like to share. It’s when you’re talking about aloneness and how “the alien planet of solitude had a gravitational pull” on you ever since you were a child. You go on to write: “Each one of us was stuck on our own planet – we each were our own planet – and any attempt to squash two planets together would result not in a new planet, but in a catastrophic collision in the cosmos…[b]etter to be like binary stars, two celestial bodies orbiting around a common center, existing on their own together. Looking up into the night sky with your naked eyes, binary stars appear to be a single point of light, but they are in fact two separate entities, connected by the space between them, not divided by it.”

I was so struck by this – by both its beauty and truth. Can you elaborate on this metaphor? How does this understanding help us form healthy, meaningful relationships or connections with others? How does an acceptance of solitude prevent a “catastrophic collision” from happening?

No matter how much time you spend with people, no matter how close you are to someone, the fact remains that you have access to a universe that no one else can see. You, alone, are the witness to the countless thoughts of your mind, the worlds those thoughts create, the stories you then live out because of your belief in those thoughts. You, alone, are the inhabitant of your body, feeling the countless sensations it is subject to. You, alone, go with you wherever you are. Even if you have a conjoined twin, your twin does not see from your perspective. We are, each of us, alone, but we are alone together. Which is not to say we are separate. But we are alone with ourselves.

The work of being human seems to revolve around this work of coming home. Coming home to myself, no longer looking to be someone else or somehow else or somewhere else. Receiving this moment, this life, this birth, this death. Having the courage to stop and listen, the courage to greet myself as the beloved I have been longing for. If I am in relationship with myself and my life in this way, then I have relieved my partner of the burden of having to fill the existential hole of my longing, or be some reliable answer for all my questions, the reason for my being. What a burden to put on another person. If I understand that I am my own planet, and that there is no way not to be, then I can begin the work of exploring and understanding this planet that I am. I can be open to learning the planet that you are, rather than trying to fix my planet or suck you into mine. I become curious, instead of needy. Trusting instead of desperate.

A part of this work might mean encountering the territory where I wish, more than anything, that I wasn’t my own planet. That longing to merge, to be one, to be with. This work then simply asks me to know this territory, know that it is a part of my planet, but not the only part. It is a mind-state based on the assumption that I am somehow separate from everything else in the cosmos.

This is where the metaphor isn’t quite right. Because, in the end, there is only one planet. I am inextricably connected to and a part of everything, as are you, as is everything. None of us are immune or inured, in a vacuum, somehow separate. The food I eat becomes me. That food came from the earth and the rain and the sun. My ancestors. All my relationships. We are a part of the vast, untraceable web of interbeing. We are that web. And yet, no one else is experiencing me, my life, what it is to be Andrew. And so, how to hold both? How to wed my own solitary life, and how to remember that my life is not my own?

And to the last part of your question: sometimes there is no stopping “catastrophic collisions,” even if you are deeply engaged in the work of contemplation and self-inquiry. Sometimes, shit just hits the fan and that’s how it goes. Maybe that’s how it needed to go. Don’t be too careful. A part of being vulnerable is colliding into the people we love. That’s learning. And loving, perhaps, uses the collisions as a way to expand what it is capable of including. So, if it’s a catastrophic collision you seem to be approaching, consider the etymology of the word “catastrophe”—from the Greek katastrophē, an overturning, ultimately from kata, down, and stréphein, to turn. Catastrophe is not some bad thing. It is an overturning that comes from getting taken down. And sometimes we need to get turned over to grow. The soil certainly does. If it takes getting taken down to get turned, so be it.

9. I wanted to ask you about your life immediately following your walk. I didn’t want your book to end! What was your transition back into reality like? During your walk through the Navajo Nation, you met a man named James who said about your return home, “It’s going to be hard for you…because you’ve seen so many other things which will probably change you. They say you can never go back to being who you were before.” Was returning home challenging? How were you a changed man?

By the time I got to the Pacific Ocean, I was tired. I didn’t want to be walking 20 miles a day anymore, didn’t want to be as alone as I was on the road, didn’t want to be clueless about where I’d be sleeping most nights. I was ready to be at home in a place, which is what I’m doing now in western Massachusetts.

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of my life now is the proclivity to create a bubble and then stay in it. That’s what I loved most about my walk, how each day the bubble was shattered. I was out and exposed, meeting all different kinds of people everyday, being forced to learn different spiritual, emotional, and ideological languages. I wonder often: how do I continue to put myself out there when I’m not traveling? How do I continue to catalyze connection when I’m not wearing a sign on my back that says, “Walking to Listen”? How do I become a steward of this land and a good host to my specific community, while staying open and unattached? Each day is an answer to this living question.

10. Finally, can you tell us a little bit about what you’re doing now and how your walk helped shape that? I know that you’ve been facilitating workshops and giving speeches on listening – teaching others what listening is and how to listen. So, what is listening? And how do we listen?

I got a glimpse of the world that becomes possible with an ability and willingness to listen. It’s a gorgeous world. If you see something magnificent, you’d want to tell people about it, right? If you went out west and saw the Grand Canyon, and then came back home and realized your people had no idea the Grand Canyon existed, you’d want to tell them! You’d show them pictures, tell them stories, do whatever you could to tell them about this special place, and urge them to go there, if ever they could. This is how I feel about listening—the work of sensitizing yourself such that you can listen to what’s actually going on in your own mind and heart; the work of listening to the earth and what she is asking of you; and the challenging, healing work of listening to each other.

I’ve also realized that listening is something that has to be learned, which means that it’s possible to not learn it. The only way to teach it is to do it. So I’m just continuing to listen in my own little life as best I can, and trying to take this work into spaces where we can explore that magnificent world together in a workshop setting. I am learning.

I’ve also realized that listening is something that has to be learned, which means that it’s possible to not learn it. The only way to teach it is to do it. So I’m just continuing to listen in my own little life as best I can, and trying to take this work into spaces where we can explore that magnificent world together in a workshop setting. I am learning.

I have a lot I could say about what listening is, but I feel compelled to invite you to find out what listening is for yourself instead. And how to do it? It begins with the courage it takes to look inward and then communicate what you find there in the form of a sincere question. Whether or not whoever you’re with joins you in the journey to connection is irrelevant. What matters is that you went there. It’s wonderful when they join, but you do not need them in order to go there, to the heart. Go there yourself and abide there, and the rest will take care of itself.

Thank you for honoring me with such open wondering, your sincerity, and for inviting me to this magnificent world with you. What a gift! Peace to you in your walk today.