I first read Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s* Gift from the Sea in my late twenties, early thirties when I was a busy young mother of three with an innocent, idealistic view of the world and the life I had ahead of me.

I first read Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s* Gift from the Sea in my late twenties, early thirties when I was a busy young mother of three with an innocent, idealistic view of the world and the life I had ahead of me.

I remember it as a neat little book that spoke to the duties and responsibilities of raising children, and the never-ending business of making and keeping a home. I remember thinking to myself how lucky she was, as a mother of five children, to be staying at a beach house by herself with enough time to compose such beautifully expressed sentiments, written in such a calm, lyrical and soothing manner.

I read her book with the eyes and mind of a young, inexperienced and naive woman, mother and wife who had little knowledge of the trials and tribulations that life’s journey would inevitably bring.

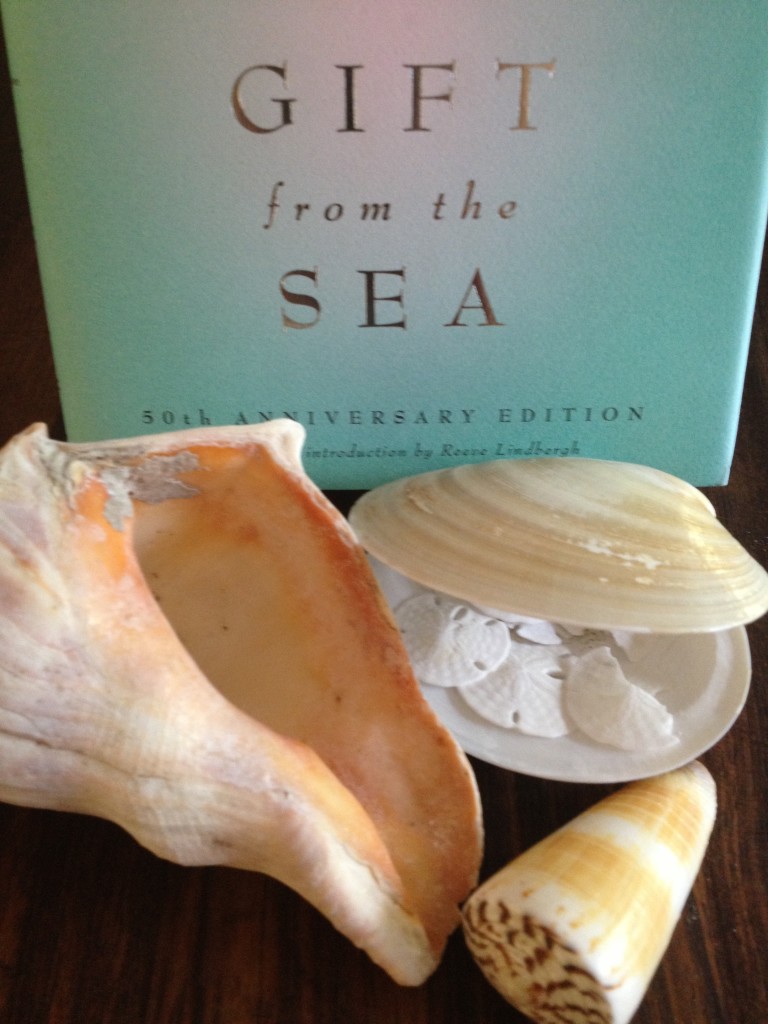

Now some 25 years later, with a greater understanding and clarity that only a lifetime of experience can provide, I have a faint remembrance of the “gifts” that Ms. Lindbergh’s musings offered. And so, when I spotted Gift from the Sea in an island gift shop neatly displayed on a seaside-themed table in a soft ocean blue jacket cover – with an introduction by her daughter Reeve Lindbergh for the book’s 50th anniversary edition – I was drawn into a second much-later-in-life reading.

Like any classic work of art, Gift from the Sea bestows upon its readers timeless wisdom and insights, capturing both the beauty and frailty of the human condition, making it just as pertinent today as when it was first published in 1955.

As is so often the case with such books, the experience of reading it as a young woman compared to rereading it in the later years of one’s life is vastly different. And therein lies the book’s greatest “gift”: the ability to speak to us at various stages along our own journey – with a light or heavy heart – reminding us of the “gift” of life itself.

Below is an excerpt that I found to be particularly relevant in today’s world:

To be a woman is to have interests and duties, raying out in all directions from the central mother-core, like spokes from the hub of a wheel. The pattern of our lives is essentially circular. We must be open to all points of the compass: husband, children, friends, home, community; stretched out, exposed, sensitive like a spider’s web to each breeze that blows, to each call that comes.

How difficult for us, then, to achieve a balance in the midst of these contradictory tensions, and yet how necessary for the proper functioning of our lives. How much we need, and how arduous of attainment is that steadiness preached in all rules for holy living. How desirable and how distant is the ideal of the contemplative, artist, or saint — the inner inviolable core, the single eye.

With a new awareness, both painful and humorous, I begin to understand why the saints were rarely married women. I am convinced it has nothing inherently to do, as I once supposed, with chastity or children. It has to do primarily with distractions. The bearing, rearing, feeding and educating of children; the running of a house with its thousand details; human relationships with their myriad pulls — woman’s normal occupations in general run counter to creative life, or contemplative life, or saintly life.

The problem is not merely one of Woman and Career, Woman and the Home, Woman and Independence. It is more basically: how to remain whole in the midst of the distractions of life; how to remain balanced, no matter what centrifugal forces tend to pull one off center; how to remain strong, no matter what shocks come in at the periphery and tend to crack the hub of the wheel.

What is the answer? There is no easy answer, no complete answer. I have only clues, shells from the sea. The bare beauty of the channelled whelk tells me that one answer, and perhaps a first step, is in simplification of life, in cutting out some of the distractions. But how? Total retirement is not possible, I cannot shed my responsibilities. I cannot permanently inhabit a desert island. I cannot be a nun in the midst of family life. I would not want to be.

The solution for me, surely, is neither in total renunciation of the world, nor in total acceptance of it. I must find a balance somewhere, or an alternating rhythm between these two extremes; a swinging of the pendulum between solitude and communion, between retreat and return. In my periods of retreat, perhaps I can learn something to carry back into my worldly life. I can at least practice for these two weeks the simplification of outward life, as a beginning.

See our collection of “gifts from the sea” below:

Anne Morrow Lindbergh was an author, pilot and journalist who was born in New Jersey in 1906. Her father, Dwight Morrow was a partner in the banking house of J.P. Morgan & Co. and was a New Jersey Republican senator in the 1930’s while her mother, Elizabeth Reeve Morrow, a teacher and poet, served as acting president of Smith College 1939-1940. Anne Morrow married Charles Lindbergh in 1930, the most famous man in the world after he completed the first-ever nonstop solo transatlantic flight in 1927.

Ms. Lindbergh went on to become the first woman ever to obtain a glider pilot’s license and spent a lifetime flying around the world with her aviator husband, serving as his copilot on mission trips to conduct research for aviation companies. She wrote of their aerial adventures in her first book North to the Orient.

Many will remember Anne and Charles Lindbergh for the tragedy that happened in 1932 when their first-born child, just two years old was kidnapped from his crib. Known as the “Crime of the Century”, the family was eventually forced to move to England to escape the overwhelming fascination with their case and with threats against their second son.

In England they went on to have five more children and in 1955 she published Gift from the Sea, a “philosophical meditation on women’s lives” in the twentieth century. It was on the New York Times bestseller nonfiction list for eighty weeks and sold five million copies in hardcover and paperback during its first twenty years.

Continue delving into all things life wisdom from:

-

Life’s Journey According to Mister Rogers

-

Social Graces: Words of Wisdom on Civility in a Changing Society

-

8,789 Words of Wisdom

-

Grit: the Power of Passion and Perseverance

-

Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World

-

The Road to Character

-

The Shepherd’s Life

-

Napoleon: A Life

-

the Knights Code of Chivalry

-

living the aloha spirit

-

and from these military excerpts, creeds and poems

-

in addition to these quotes about the importance of planning

-

and these quotes on teaching, thinking and learning

-

finally, a personal message for college graduates