With President Obama turning toward the mirror in the White House and Russian President Vladimir Putin turning toward Ukraine, in an apparent attempt to reinstate Russia’s “sphere of influence”, we at ATG turn to the book, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (2003), an entertaining historical account of one of Putin’s earlier, yet equally unpredictable and erratic predecessors: Nikita Khrushchev.

With President Obama turning toward the mirror in the White House and Russian President Vladimir Putin turning toward Ukraine, in an apparent attempt to reinstate Russia’s “sphere of influence”, we at ATG turn to the book, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (2003), an entertaining historical account of one of Putin’s earlier, yet equally unpredictable and erratic predecessors: Nikita Khrushchev.

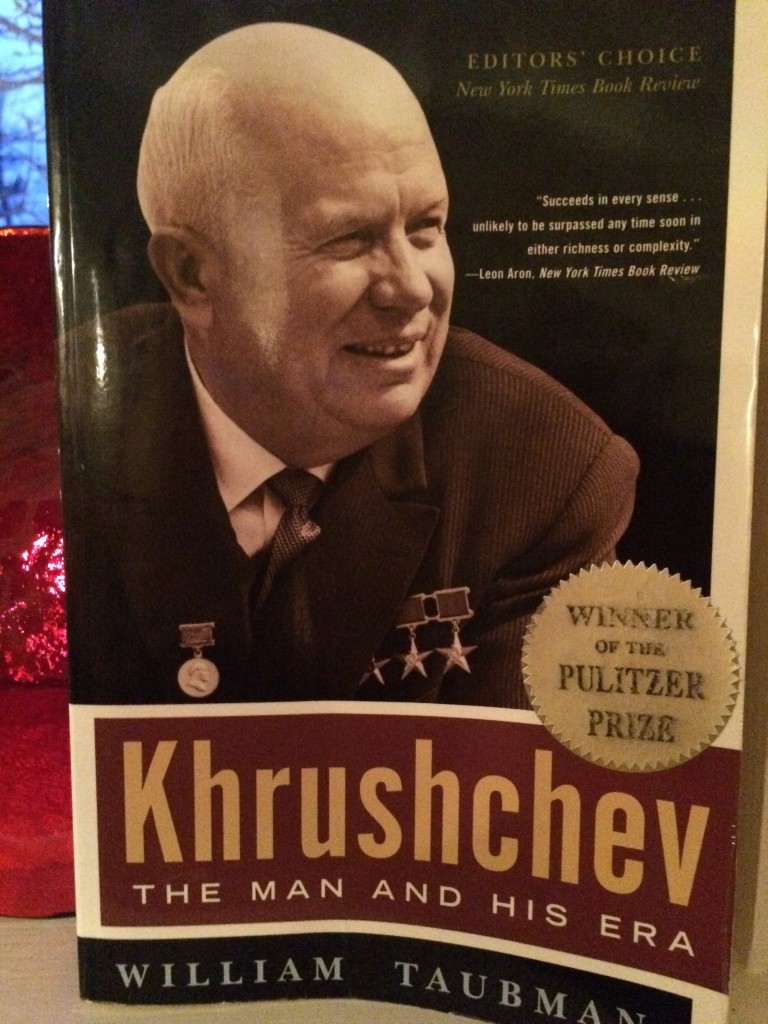

Written by William Taubman, it won the Pulitzer Prize for biography in 2004 and has been referred to as “one of the best books ever written on the Soviet Union” (Ian Thomson, Irish Times). It is a book that has retained a prominent position on our bookshelf, not only for the light it sheds on the fascinatingly complex character of Nikita Khrushchev, but for its easily accessible insight into the Bolshevik ideology and depiction of a communist society.

Written and “exhaustively researched” with interviews from Khrushchev’s children, grandchildren and other relatives over the course of 10 years, it is a “truly masterful biography” that presents a “lively narrative” likely to remain “the standard study of the man who in February 1956 started the de-Stalinization with the ‘Secret Speech’ that he delivered to the 20th Communist Congress that 35 years later ended in the collapse of the Soviet Union” (Richard Pipes, New York Times).

Indeed, Taubman’s book is an unexpectedly, yet highly entertaining read that “pulls back the curtain” on the period in Russia’s history that is referred to as the “Soviet Era” (i.e. 1917 after the Bolshevik’s overthrow of Nicholas II at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg to 1991, when the USSR disintegrated into 15 separate countries).

Taubman shows how Khrushchev’s colorful, contradictory, insecure and impulsive personality “led the Soviet Union with foreign policies driven not by some well formulated plan, but by an inner psychological warfare.”

It is Khrushchev’s psychological warfare that Taubman unveils so beautifully. Finding his “personality more fascinating than his foreign policy,” he takes the reader from Khrushchev’s humble peasant beginnings in the early 1900s, to his joining of the Bolshevik party in 1918, to Stalin’s inner circle, where he became complicit in Stalin’s crimes, to his appointment as Prime Minister in 1958, and, finally, through his retirement, tormenting guilt, and death in 1964.

The most entertaining and enlightening part of Taubman’s book, however, comes in his chapter on Khrushchev’s trip to the United States in 1959, where the complexity of both Khrushchev’s character and the Soviet Union is so astutely captured and revealed.

Indeed, Khrushchev’s trip to America – deemed by Soviet chroniclers “the thirteen days that stirred the world” and a “triumphant journey” that had “no precedent in history” – was truly an eye opening experience not only for the Soviet himself, but for the United States government who, in an attempt to understand his repeated volatile behavior, ended up hiring twenty psychiatrists and psychologists.

Perhaps most telling of Khrushchev’s personality is the deliberation he gave to choosing which plane he should take to America, weighing the pros and cons of various types to determine which one would make the most lasting impression. “The Ilyushin 18 jet would require embarrassing stops for re-fueling” and “Tupolev 114 could reach Washington nonstop but was found to have microscopic cracks in the engine.”

So, as Taubman explains, Khrushchev landed on the “Tu-104”, considered to be the tallest plane in the world, “because of the triumphal appearance he imagined it would make when landing in Washington.”

But, then comes the irony. “Little did [Khrushchev] know because no one dared tell him,” Taubman writes, “that one reason the plane was so high off the ground was to keep its engines from ingesting stones, dirt, or other debris on unkempt Soviet runways.”

Yet, this was just one example of Khrushchev’s inferiority complex. As Taubman writes, during his trip, Khrushchev was resolved “not to be amazed by the grandeur of America… ”

Yet, this was just one example of Khrushchev’s inferiority complex. As Taubman writes, during his trip, Khrushchev was resolved “not to be amazed by the grandeur of America… ”

At the formal state dinner, he declared: “It is true that you are richer than we are at present. But tomorrow we will be as rich as you are.”

And “[w]hen his train passed in plain view of the Vandenberg Air Force Base, [Khrushchev] refused to look, telling journalists that ‘we have more of these bases than you have and, besides, they’re much better equipped.’”

Yet, as bold, insecure and complex as Khrushchev was, he also struggled a great deal with guilt throughout his life, particularly in retirement. “After I die,” Khrushchev said toward the end of his life, “they will place my actions on a scale – on one side evil, on the other side good. I hope the good will outweigh the bad.”

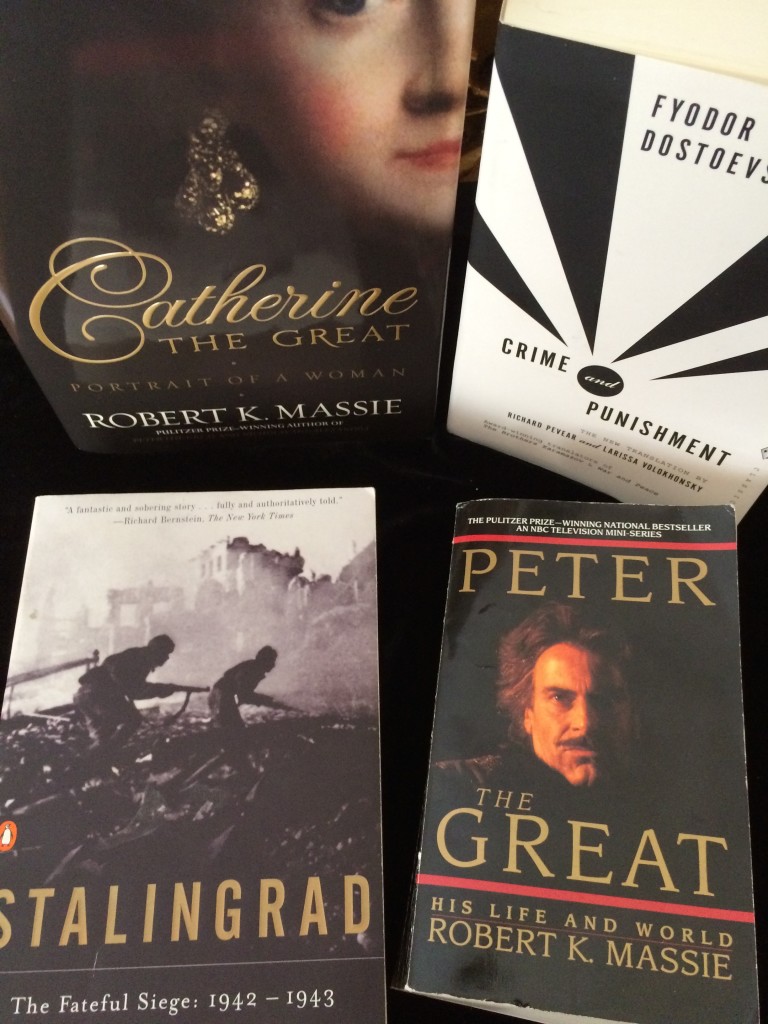

That Khrushchev felt guilty for some of his actions and the wrongs he had committed was not necessarily surprising, for, as Richard Pipes so eloquently states in a New York Times book review: “There is something very Russian about this story of crime and self-inflicted punishment.”

Wrong on the last comment about how some Americans think the press here is on par with Pravda of Krushchev’s time. I’d say the press here was far worse. Everyone knew what Pravda was but here, there is the ctoninuing attempt at subterfuge by the MSM to falsely represent themselves as unbiased news purveyors. By the time Kruschev reigned, there was no one that stupid in the USSR that didn’t know that Pravda was a joke. Here, far too many people still can’t completely get away from thinking that NBC et al are fair arbiters and not Obama’s henchmen.

That was interesting. I wctahed all the way to Film 2, Part 3, but it never really did get back to what I would have liked to see the most the faces of the people on the street watching Khrushchev’s motorcade what they looked like when they actually saw him. Obviously there were a few people out there holding anti-Communist signs, but the average reaction, whether curiousity, or applause or dislike, could be even more telling.One thing I did notice: Khruschev’s translator looked like he was about to have a nervous breakdown I guess that’s one job you wouldn’t want to botch.Thanks, Steve!

Sounds like a great read!