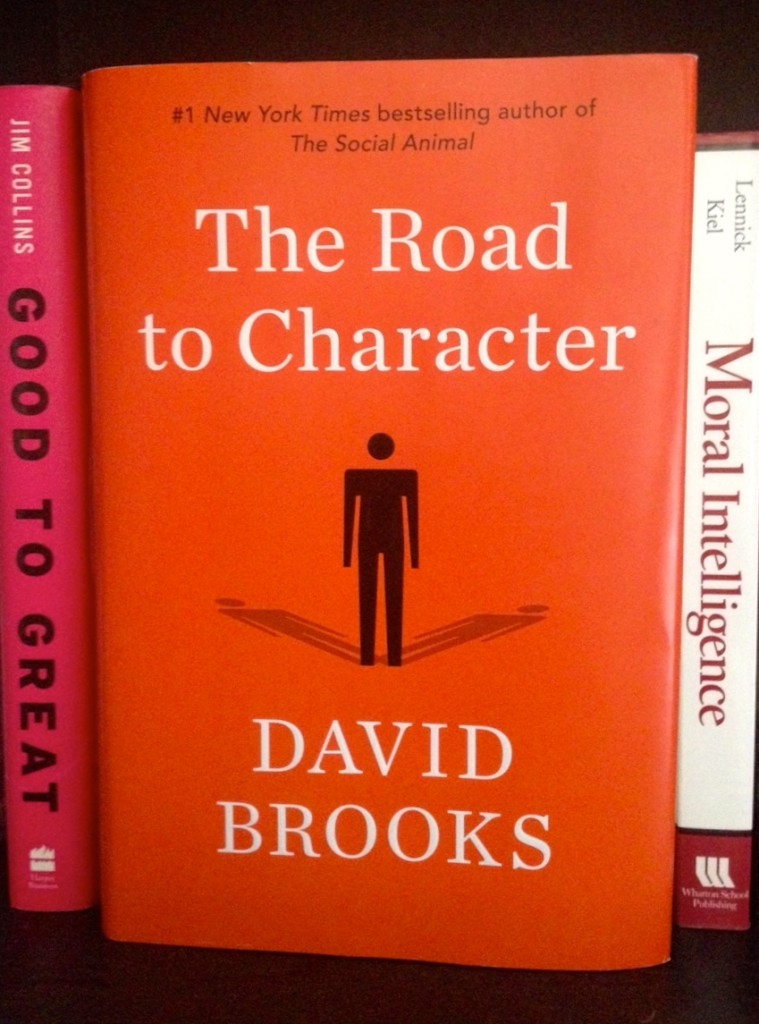

“We are out of balance,” declares David Brooks, the widely recognized New York Times columnist, in his new book The Road to Character:

“We are out of balance,” declares David Brooks, the widely recognized New York Times columnist, in his new book The Road to Character:

“The mental space that was once occupied by moral struggle has gradually become occupied by the struggle to achieve. Morality has been displaced by utility. Adam II [our internal, morally concerned nature] has been displaced by Adam I [our external, career-oriented nature].”

In an eye opening, beautifully written exploration into the development of a strong inner character, David Brooks shows how far we have strayed from the “crooked-timber” school of thought that deliberatively recognized human limitations and fallibility and encouraged the cultivation of virtues such as humility, selflessness, generosity and self-sacrifice.

While he dedicates a large portion of his book to examining the process of character building through the lives of ten great thinkers – such as Dwight Eisenhower, Dorothy Day, St. Augustine, George Eliot – it’s the last chapters that give this book its due merit.

Using data, history and the beliefs espoused by past and current philosophical movements as evidence, Brooks reveals a startling moral ecology permeating our culture today: one that places more of an emphasis on individual success and achievement than on inward development and self-confrontation.

It’s not that we’re bad or more selfish or venal than people in other times, Brooks writes. It’s that we’ve become “morally inarticulate” and have “lost the understanding of how character is built.”

What was once deemed essential by the “crooked-timber” tradition – an awareness of weaknesses, a waging of an internal struggle against sins and a rejection of self-glorification – has been marginalized by the pervasive force of the “Big Me” culture that encourages self-liberation, self-expression and self-promotion, entrusting the self with a moral code and worldview based on what feels good or right.

It’s an ethos that frees us from the weight, even consideration, of internal weaknesses, epitomized in the mantras: “I am lovable and capable” and “I am worthy and special.”

Brooks writes: “The self is less likely to be seen as the seat of the soul, or as the repository of some transcendent spirit. Instead, the self is a vessel of human capital. It is a series of talents to be cultivated efficiently and prudently. The self is defined by tasks and accomplishments. The self is about talent, not character.”

While our current moral tradition, he continues, “tells you how to do things that will propel you to the top,” it “doesn’t encourage you to ask yourself why you are doing them. It offers little guidance on how to choose among different career paths and different vocations, how to determine which will be morally highest and best. It encourages people to become approval-seeking machines, to measure their lives by external praise…”

What we are left with, therefore, is a moral ecology that builds up – encourages, praises and endorses – the exterior, defining people by their abilities and achievements while neglecting the inner formation of one’s self and the development of moral faculties essential to leading a meaningful life.

“The achievement machine rewards you if you can demonstrate superiority – if with a thousand little gestures, conversational types, and styles of dress you can demonstrate that you are a bit smarter, hipper, more accomplished, sophisticated, famous, plugged in, and fashion-forward than the people around you,” he writes.

Accordingly, it is no longer a question of “how can I combat my weaknesses” so much as it is a question of “how can I use this opportunity, person or experience” for my own personal advancement.

While Brooks highlights the adverse effects of such a moral shift – among them an unhealthy rise in narcissistic and self-aggrandizing tendencies – he gives fair recognition to the advantages of such “meritocracy”, noting that it has “liberated enormous energies” and corrected some deep social injustices.

The problem, however, is that it’s just gone too far.

“To live a decent life, to build up the soul, it’s probably necessary to declare that the forces that encourage the Big Me, while necessary and liberating in many ways, have gone too far. We are out of balance. It’s probably necessary to have one foot in the world of achievement but another foot in a counterculture that is in tension with the achievement ethos.”

A fascinating read, particularly for those interested in understanding the philosophical underpinnings that form a society and culture, The Road to Character is made all the more poignant with an awareness that it was written by someone in search of a greater depth.

Describing himself as being “born with a disposition toward shallowness” who has “lived a life of vague moral aspiration” and had to “work harder than most people to avoid a life of smug superficiality,” there is something affecting in Brooks’ diligent attempt to understand how to live a rich inner life – and in his admission that he “wrote [the book], to be honest, to save my own soul.”

Continue delving into all things character building with:

-

Gift from the Sea

-

Social Graces: Words of Wisdom on Civility in a Changing Society

-

8,789 Words of Wisdom

-

Grit: the Power of Passion and Perseverance

-

Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World

-

Life’s Journey According to Mister Rogers

-

The Shepherd’s Life

-

Napoleon: A Life

-

the Knights Code of Chivalry

-

living the aloha spirit

-

and from these military excerpts, creeds and poems

-

in addition to these quotes about the importance of planning

-

and these quotes on teaching, thinking and learning

-

finally, a personal message for college graduates

This book is a very interesting and highly pertinent read and your review was excellent!