“Something strange is happening at America’s colleges and universities. A movement is arising, undirected and driven largely by students, to scrub campuses clean of words, ideas, and subjects that might cause discomfort or give offense.”

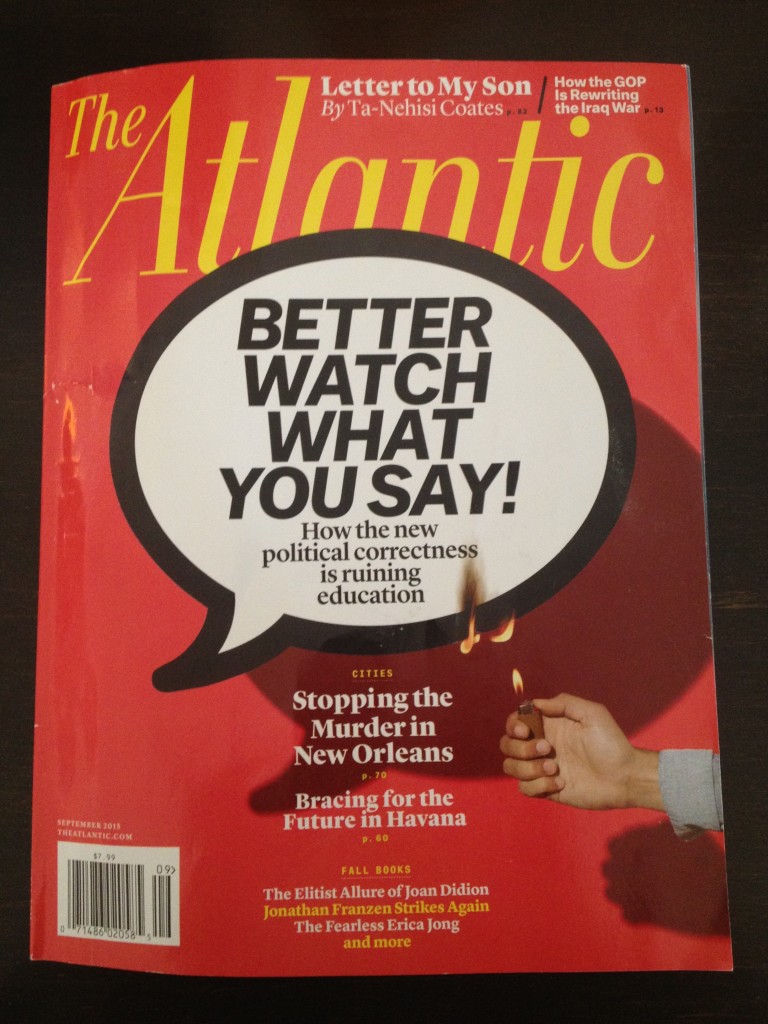

So begins an article in the September issue of The Atlantic Magazine, written by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt entitled, “The Coddling of the American Mind”, in which they provide an in-depth look into the “trigger warnings”* and “microaggressions”* movement that is becoming institutionalized across U.S. college campuses, subsequently “affecting what can be said in the classroom, even as a basis for discussion.”

So begins an article in the September issue of The Atlantic Magazine, written by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt entitled, “The Coddling of the American Mind”, in which they provide an in-depth look into the “trigger warnings”* and “microaggressions”* movement that is becoming institutionalized across U.S. college campuses, subsequently “affecting what can be said in the classroom, even as a basis for discussion.”

From the works of classic literature and paintings by renowned artists (such as the painting of Ulysses tied to the mast of his ship in which there were topless mermaids that Mr. Haidt used in one of his classes for a lesson on the weakness of the will, only to receive a formal complaint) to seemingly innocuous statements, such as “America is the land of opportunity,” Messrs. Lukianoff and Haidt describe an uncomfortable and disturbing environment where professors, threatened with formal punishments or the loss of their jobs, are left teaching in classrooms where their every word is policed by students who are dictating what academic resources are acceptable.

Messrs. Lukianoff and Haidt cite an article written by seven humanities professors who noted that the trigger warning movement was “already having a chilling effect on their teaching and pedagogy.”

Even popular comedians, such as Chris Rock, Jerry Seinfeld and Bill Maher, are refusing to perform on campuses and have “publicly condemned the oversensitivity of college students, saying too many of them can’t take a joke.”

In a rather telling statement, Messrs. Lukianoff and Haidt cite an essay published in Vox by a professor entitled, “I’m a Liberal Professor, and My Liberal Students Terrify Me.”

“The dangers that these trends pose to scholarship and to the quality of American universities are significant,” they write, “and sometimes seem ‘surreal.’”

Surreal they certainly are. But, it becomes all too clear in reading their article that this trend – where students’ emotional well-being in essence trumps reality – is no joking matter.

The mentality perpetuating such a movement is one of “intellectual homogeneity,” where students rarely “encounter diverse viewpoints” and maintain the attitude that there is nothing to learn from “people they dislike or from those with whom they disagree.”

“The ultimate aim, it seems, is to turn campuses into ‘safe spaces’ where young adults are shielded from words and ideas that make some uncomfortable,” writes Messrs. Lukianoff and Haidt.

In the section, “How Did We Get Here,” they explain the importance of understanding the difference between the Socratic method of teaching, in which students are taught how to think, and the “emotional reasoning” that is being embraced by this movement, in which students are taught to “think in a very different way,” and which is perhaps leading to pathological thinking.

“The Socratic method is a way of teaching that fosters critical thinking, in part by encouraging students to question their own unexamined beliefs, as well as the received wisdom of those around them. Such questioning sometimes leads to discomfort, and even to anger, on the way to understanding.”

“On the way to understanding” is a key phrase for its implication of a journey undertaken; learning, scholarship and the attainment of wisdom is almost always a rigorous journey that involves discomfort, pain and sometimes even anger.

A coddled environment of “vindictive protectiveness” that punishes anyone who makes people feel uncomfortable and where feelings guide one’s interpretation of reality – “emotional reasoning is now accepted as evidence,” writes Messrs. Lukianoff and Haidt – is a manufactured environment of suppression that fosters a distorted view of reality.

Such distortion, augmented by our hopes and fears, is something that the ancient philosophers understood well; Buddha once said, “Our life is the creation of our mind” and Marcus Aurelius, “Life itself is but what you deem it.”

But the life that an unfettered mind deems can often lead to an inaccurate reading of the world and reality, not to mention mental instability and illness. Messrs Lukianoff and Haidt remind us that “subjective feelings are not always trustworthy guides; unrestrained, they can cause people to lash out at others who have done nothing wrong.”

In fact, many mental health professionals are seeking to help patients by utilizing “Cognitive Behavior Therapy” – a “modern embodiment of this ancient wisdom,” with a goal, similar to that of the Socratic method of teaching, to “minimize distorted thinking and see the world more accurately.”

“[C]ognitive behavioral therapy teaches good critical-thinking skills, the sort that educators have striven for so long to impart,” Messrs. Lukianoff and Haidt write. “By almost any definition, critical thinking requires grounding one’s beliefs in evidence rather than in emotion or desire, and learning how to search for and evaluate evidence that might contradict one’s initial hypothesis.”

As we write, protests are – and have been – taking place on college campuses with students’ pleas for safer and more sensitive environments. So far, one university president (Timothy Wolf of the University of Missouri) has resigned and it will be no surprise to see others follow suit. Where it will all lead is anyone’s best guess.

But, this much is clear: Messrs. Lukianoff and Haidt have shed light – with evidence, accuracy and an undistorted view – on the reality of a movement that has been percolating for years and is just now beginning to unfold.

There is, however, a silver lining.

*Microaggressions are defined as “small actions or word choices that seem on their face to have no malicious intent but that are thought of as a kind of violence nonetheless”; trigger warnings are “alerts that professors are expected to issue if something in a course might cause a strong emotional response.”

*Greg Lukianofff is a constitutional lawyer and the president and CEO of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, which defends free speech and academic freedom on campus. He is the author of Unlearning Liberty.

*Jonathan Haiadt is a social psychologist who studies the American culture wars and is a professor in the Business and Society Program at New York University’s Stern School of Business. He is the author of The Righteous Mind and The Happiness Hypothesis.

For a similar piece, see also: “Bonfire of the Academy“, Wall Street Journal, Nov. 2015